We often receive questions about our use of terms like “corrupt” or “unethical” when referencing certain Judges. Some presume that advocates might just be exaggerating, driven by adverse decisions in individual cases. However, this perception is misplaced. When the so-called “terrible three” – Unger, Ichikawa, and Carringer – presided over the Family Court Bench, there was a discernible pattern of bias in rulings, especially in custody cases intertwined with claims of domestic violence and abuse.

These actions repeatedly compromised the safety of victims, leading to severe injuries, gross negligence, child abuse, and even murder / manslaughter.

These Solano County Family Law Judges even went so far as to to accuse victims of fabricating evidence, all in an attempt to sidestep (or leverage) the mandates of Family Code 3044.

Solano County’s flawed handling of DV cases is both longstanding and well-documented. It’s worth noting that, in the past, the County obtained federal grants from the DOJ Office on Violence Against Women, while often routinely and predictably denying protective orders in cases with concurrent custody proceedings.

In our history of advocacy we have seen Solano County Judges leverage DVROs and Family Code 3044, to manipulate outcomes of custody cases involving allegations of domestic violence.

We’re not sure why it happens, but we know it happens. Judges have refused to grant DVROs, in cases with clear evidence of Domestic Violence if they wanted to ensure the alleged perpetrator of violence maintained custody. Judges have also inappropriately prolonged and continued DVROs when they wanted to ensure the alleged perpetrator of violence did not have custody, sometimes violating Family Code and ignoring appellate law in doing so.

Buckle up, because this gets long.

We’ve mentioned before that Judge Garry Ichikawa was overturned on appeal. This is important because he held himself to be a champion of DV victims, and was notably pursuing the idea of a Domestic Violence Court (which never really came to fruition). It seemed that him being overturned on appeal ignited a spark that accelerated this pattern of leveraging DV cases to engineer custody outcomes.

Years ago, we randomly sampled hundreds of cases in Solano County – not handpicking cases, but random sampling. We looked at the rate at which DVROs were filed and granted. We noticed a discernible difference in the rate at which DVROs were granted when the parties also had a custody case pending, vs no custody case. For some judges, the discrepancy was low, 5-7 percentage points, but for other judges (the terrible three), the discrepancy was striking – 15 percentage points or more!

Now this isn’t perfect research, because it doesn’t grant insight into the merits of the case, the point was to validate if there was a pattern. And there was. As a litigant in Solano County, you were less likely to be granted a DVRO if you also had a custody case before the Court. We saw this, we knew this, we worked with the litigants, and now we had research to back this up.

Here’s where it gets interesting.

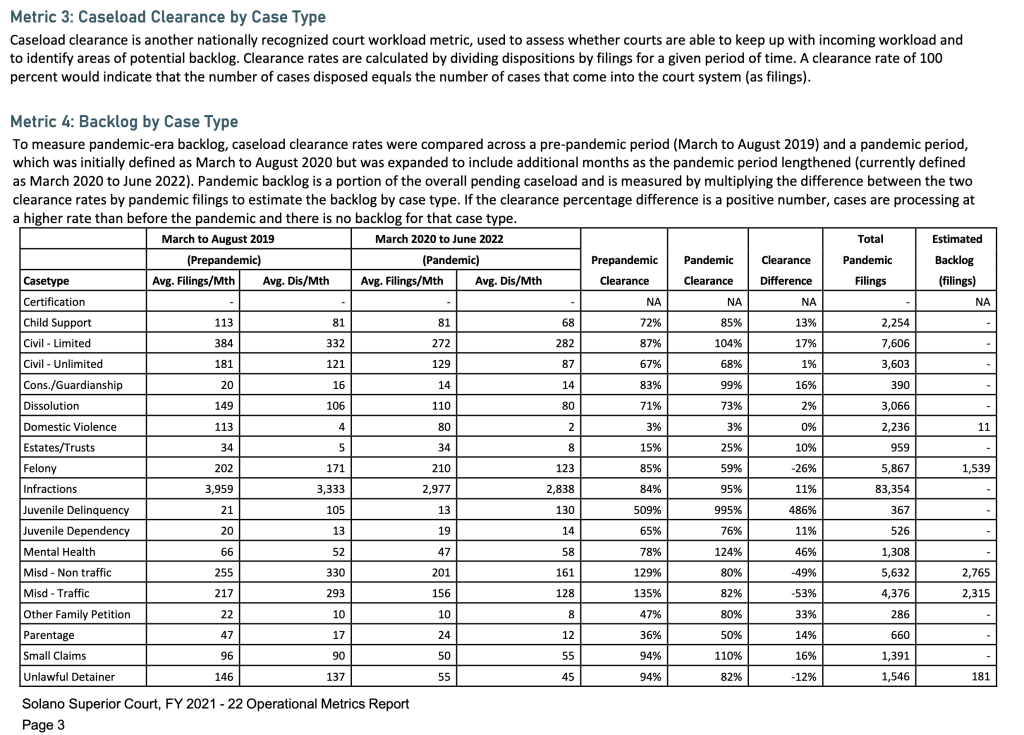

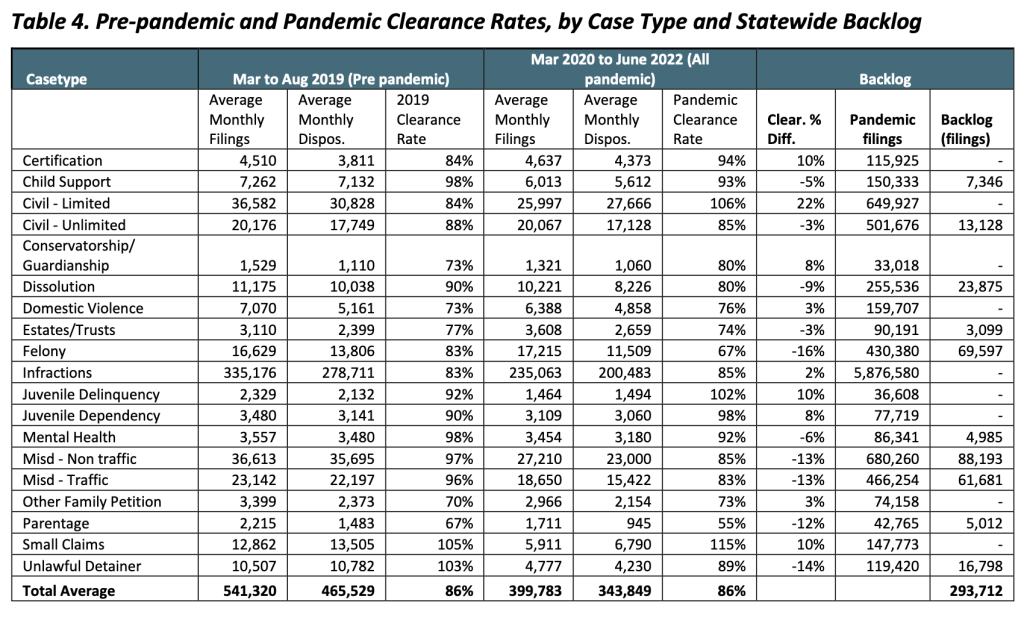

The Judicial Council of California published the disposition rates of court cases by type, by County

Metric 2: Time to Disposition by Case Type

Trial Court Operational Metrics: Year One Report Page 4

Metric 2: Time to Disposition by Case Type

Time to disposition, the percent of cases resolved within a certain time frame, is a nationally

recognized metric of court caseflow management that helps courts assess the length of time that

it takes to bring cases to disposition. 3 Standard 2.2 of the California Rules of Court established

case disposition time goals for civil and criminal cases. 4 These data are updated and reported

annually in the Court Statistics Report. However, due to technical issues resulting from case

management system transitions, not all courts are able to report these data. 5 As courts finalize

their case management systems transitions, more courts will be able to report this data.

Follow the lead here: this report measures how long it takes the Court to “resolve” a case – from filing to clearance. Next, we will single out only Domestic Violence cases (the State’s report doesn’t differentiate DV cases also involving custody matters) and compare the disposition rates of only DV cases, across all California counties.

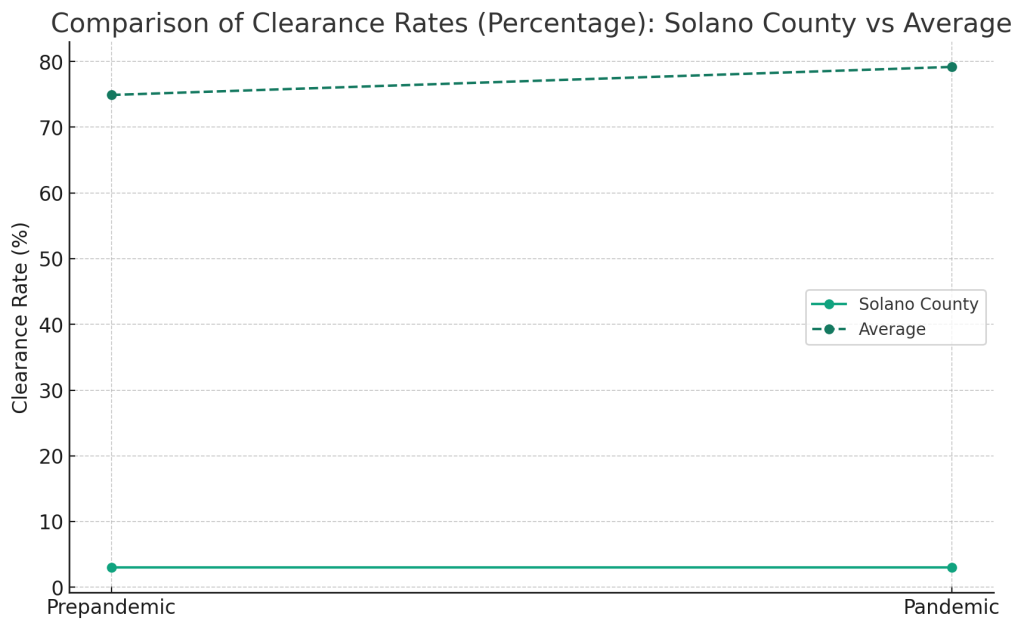

But before we get there, let’s just look at the state average clearance rates:

The state average clearance rate for Domestic Violence cases is 73% in 2019 and 76% during the pandemic.

What is Solano County’s clearance rate for Domestic Violence cases?

3%

This is the lowest rate, of any Superior Court, in the state.

One more time: this is the lowest rate, of any Superior Court, in entire state of California. The only counties with a “worse” rate are counties with so few filings, the calculations create mathematical errors (Alpine, Glenn and Sierra counties, look it up yourself).

If this doesn’t indisputably demonstrate that Solano County has a systemic problem with handling Domestic Violence cases, we don’t know what else could possibly convince you.